John Speed's Big Top Mystery

While I was poring over Richard Blome’s 1673 map of Middlesex (looking for something else entirely – the parks and enclosures I was writing about in Noble Seats & How To Spot Them) it suddenly occurred to me to wonder why he includes the image of an enormous pavilion, set in fields just to the north of London between St Giles and Clerkenwell. I don’t know how many 17th century maps of Middlesex I’ve handled over the years without really thinking too hard about a tent the size of the O2 where Holborn now is: I’ve always been intent on establishing the edition, or checking on colour or condition. With well-studied early maps of familiar places, we can fall into the trap of assuming that somebody else has already done the work, and wrung every last drop of information out of them. It’s a salutary shock to complacence, then, to find that the mystery of the tent couldn’t immediately be solved by digging through the reference library.

The pavilion makes no immediate sense on Blome’s map, and there is no illuminating explanatory note, but I assumed he was copying someone. In many ways I admire Richard Blome: I think he was ingenious and resourceful. In cash-strapped Restoration England, he produced the first new county atlas in the sixty years since the appearance of John Speed’s ‘Theatre’, but original cartography wasn’t always his strong suit; only limited funds were available for new surveys, and he relied heavily on older maps. Two questions, then: who put it there, and what does it represent? It isn’t a standard sign or symbol which we see time and again on early maps, but it is unlikely to have been unique, either; surely the meaning was clear enough for contemporary readers? Could it mark a battlefield, a fair, a hunting lodge, a venue for an event such as a summit (I’m thinking of the pavilions of the ‘field of cloth of gold’)?

We’re going to have to start 80 years earlier in 1593, with John Norden’s map of Middlesex. Norden’s map provided the model for most 17th century maps of the county – but there are no pavilions to be seen. It wasn’t his idea then. The pavilion is not on the ‘Saxton-Kip’ either, a map derived from Norden’s which was used to illustrate editions of William Camden’s history of Britain from 1607 onward (usually referred to as the ‘Saxton-Kip’ as many maps were derived from Christopher Saxton’s and engraved by William Kip, even though some maps in the series were engraved by William Hole, and some – as here – were copied from Norden).

It was John Speed who introduced the pavilion to the map. John Speed’s map of Middlesex was also based on Norden’s, but read in the context of Speed’s atlas, his ‘Theatre’, his decision to add pavilion signs makes sense. Speed was an antiquary, and intended that his atlas should be read in conjunction with his history of Britain. For that reason he included a wealth of historical detail on his ‘modern’ county maps: coins, inscriptions, coats of arms of significant local figures, battle scenes and occasional notes and descriptions. The pavilion almost certainly represents a historical event. But which?

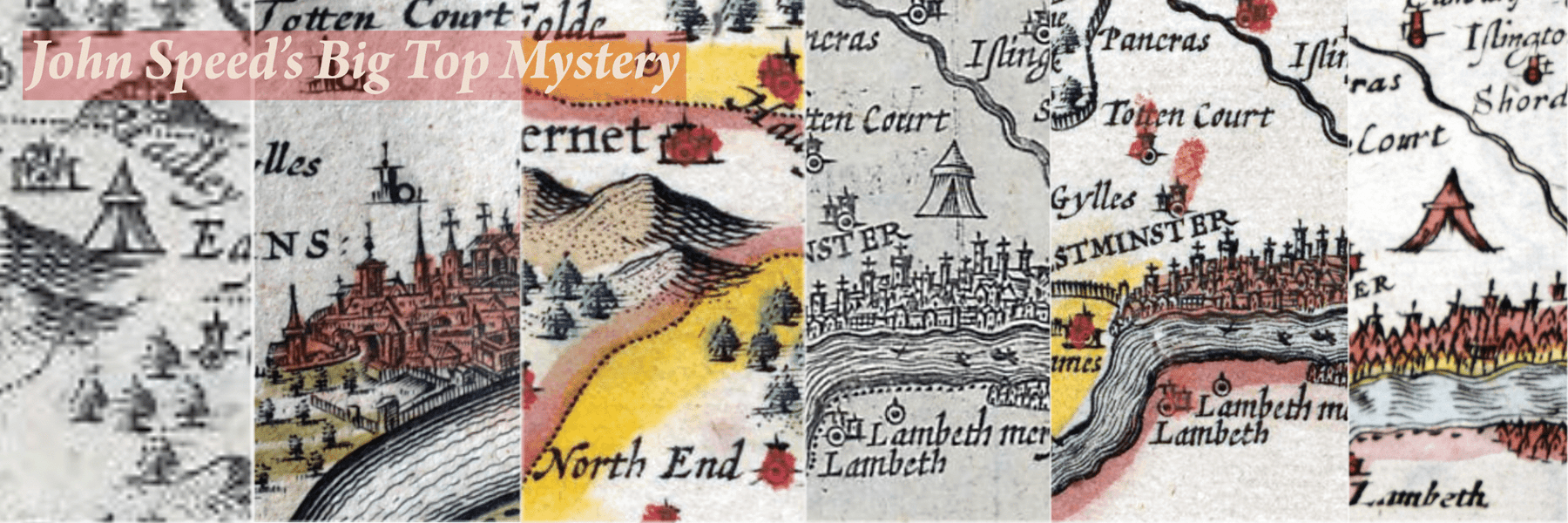

The pavilion is not on the earliest editions of John Speed’s map of Middlesex, including this proof copy printed circa 1611 which is in Cambridge University Library:

Here it is shown on Speed’s Middlesex, published after 1616, and possibly only after 1627:

Just to complicate the situation further, John Speed did not include this particular pavilion on the first edition of his Middlesex map, but whatever it represents it was important enough for Speed to take the trouble to add it later. Burnishing information from a copper printing plate, or engraving something new, is a skilled process which is rarely undertaken on a whim.

Cambridge University Library owns one of five known sets of proof maps for John Speed’s ‘Theatre’, which they have helpfully digitised. The copper printing plates were engraved in Amsterdam by Jodocus Hondius, but proof copies printed from them were sent back to London for checking. These are late proofs reflecting the state of the atlas shortly before publication, circa 1611. At this stage there is no pavilion.

The pavilion does not appear to have been added to the earliest published editions, circa 1611-16. The British Library has digitised maps from a 1616 edition (shelf mark Maps C.7.c.20) and the pavilion is still not present, but it does appear on the copy in the Crace Collection which is also held by the British Library (Maps Crace Port. 1.28). Unfortunately the example collected over 150 years ago by Frederick Crace is a loose map rather than in an atlas: it carries the early imprint of publisher George Humble, but I can’t be sure of the date. However, the pavilion is on all examples of Speed’s Middlesex I can find which were published after 1627. In other words, it was at least five years after the map’s first publication – if not longer – before Speed decided that the pavilion added something significant to the map, which was more or less self explanatory for contemporary readers and needed no further elucidation at the time.

We can now start thinking about what the pavilion might represent. Could it, for example, be a reference to Battle Bridge near St Pancras, which is one suggested site for the defeat of Boudica circa AD60? There is no mention of the revolt of the Iceni on the verso, but Speed does mention the ‘bloody’ battle of Barnet, 1471, one of the decisive engagements of the Wars of the Roses, which took place just over the border in Hertfordshire. And yes, if we look at one of the later editions of the map there is a pavilion at Barnet – so we can demonstrate that Speed uses the symbol to denote battlefields:

And if we look at the proof copy in Cambridge again? No pavilion. Now we’re getting somewhere.

But Speed doesn’t mention any other battles, and we still have the ‘Holborn’ pavilion to explain. It appears, then, at some point after 1616 it occurred to Speed (or was suggested to him) that pavilions could usefully be added to the Middlesex map to denote the sites of historical events (not just battles) referred to in the text on the verso. I have asked some learned friends and our best guess is the meeting between the rebel leader Wat Tyler and the young King Richard II at Smithfield in June 1381, which was the decisive moment in the Peasants’ Revolt. The pavilion is not in quite the right place (Smithfield is a fraction to the east, and is south of Clerkenwell) and Smithfield was known generally for Bartholomew’s Fair, tournaments and other public events, and as a place of execution. However, we are looking for a specific historical event, and the Peasants’ Revolt is one of the ‘civil broils’ referred to on the verso of the map. Speed denounces Wat Tyler's 'outrageous cruelties’ and notes that he was ‘worthily’ taken and ‘slain’ at Smithfield. At the meeting with Richard there was a scuffle, and Tyler was badly wounded by the Lord Mayor of London. He escaped but was brought back to Smithfield and beheaded there, and the revolt was swiftly crushed. Richard rescinded the concessions he had made and the threat to life, property and the established order evaporated. Very welcome for the nobility and the solid burghers of London, and one could argue that Speed is spinning triumph out of disaster by presenting this as an example of royal courage: a young king facing down the mob.

Speed’s application of symbols seems to have been pretty erratic. The Battle of Blore Heath (1459) is already marked with a pavilion on Cambridge University Library’s proof copy of the map of Staffordshire, so the idea was there from the beginning. But what about the Battle of Hastings? It is pictured on the map of Sussex, but no pavilion is to be seen anywhere near the site (further inland, at Battle) either on the proof or later editions. So some pavilions were there to start with, some added later, some never added where one might expect to see them. Some were labelled, others not. For example, on the map of Hertfordshire, a vignette shows a battle in progress directly above the pavilion marking the two battles of St Albans (1455 and 1461), which makes it very clear what is meant. On the same map, the pavilion near High Barnet is named ‘Barnet feild’, which again assists in identifying it as a battlefield site. On the Middlesex map it isn’t labelled and is in a slightly different location (the battle took place in fog, but I don’t think this accounts for Speed’s confusion). Speed’s system is far from perfect, but it is a system of sorts – we can see what he is trying to do. And what about the map-makers who copied him, such as Blome and Blaeu? Here's the 'Smithfield' pavilion as shown on Blome's 1673 map of Middlesex, which started this whole thing:

And here it is again on Joannes Blaeu’s 1645 map of Middlesex:

The two pavilions, the one we’ll now call ‘Smithfield’ and the one near Barnet, appear on the Middlesex maps published by Joannes Blaeu in Amsterdam and by Richard Blome in London – in both cases without a word of explanation on the map itself. We have to consider whether they were copied because it was felt that they added to the map, or if they were copied unthinkingly as part of the base map – along with towns, rivers and everything else. For comparison, the pavilions do not appear on the map made by Blaeu’s contemporary and rival in Golden Age Amsterdam, Joannes Janssonius, but Janssonius’ map is radically different to most 17th century maps of the county. He decided that he could fit Middlesex and Hertfordshire onto one sheet by rotating the counties, so that west is at the top of the map and north on the right. He also decided to sketch in London’s street plan, rather than showing the city pictorially. He was thinking critically about his source material, and decided that the pavilions were not relevant to what he was trying to show.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with using earlier maps as base maps, that’s how cartography evolves, but both Blaeu and Blome seem to have copied the pavilions unquestioningly. It’s very revealing about the transmission of detail from one map to another. Blome is often accused of being derivative, but Blaeu was arguably the greatest map-maker of his age. In both cases instructions to ‘copy that map in our house style’ were carried out to the letter. To be scrupulously fair it is possible that Blome and Blaeu both felt that there was sufficient information in the full text which accompanies their maps to make the meaning of the pavilions clear. Both drew heavily on William Camden’s history and John Speed’s words as well as his maps, and contemporary distinctions between history and geography were not as clear cut as they may seem to a modern audience.

Let’s test that. Richard Blome’s text for Middlesex is extensive and contains much which isn’t in Speed. For example, he brings things up to date with a mention of the Great Fire of 1666, describes a greater number of London’s principal buildings and supplies considerable information about the City Livery Companies and mercantile ventures such as the Muscovy and East India Companies. But there is no mention of Watt Tyler at Smithfield and no mention of the Battle of Barnet to explain either pavilion. Turn to the section on Hertfordshire and the Battle of Barnet is there in the text, but (unlike Speed) the pavilion does not appear on the Hertfordshire map. It really does look as though the giant tents were copied by accident.

I’m left with the sense that Speed’s pavilions weren’t especially clear to contemporaries or early copyists, let alone me. It’s all a bit haphazard. A full survey of pavilions on different states of 17th century English county maps would doubtless be useful, but as they are already dancing before my eyes it could be a while before I undertake such a thing!

Leave a comment