William Morris announces his 'pocket cathedral': a specimen leaf from the Kelmscott Chaucer

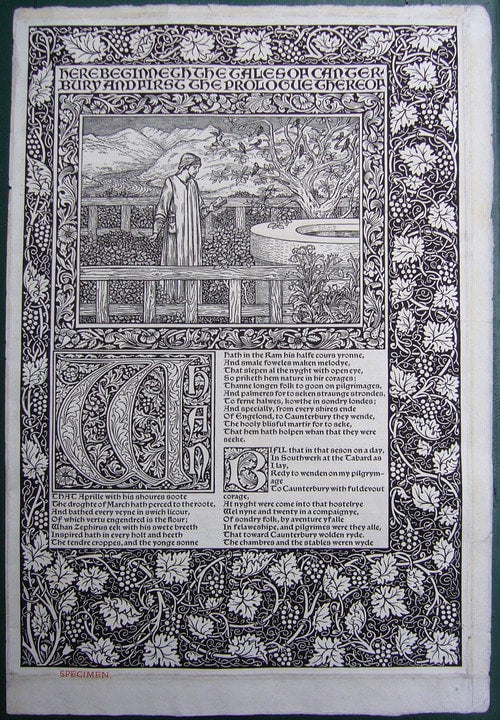

The Kelmscott Chaucer lends itself to superlatives. The first page is perhaps the most celebrated example of typography in English. It’s certainly the most famous in the context of of private press books, inspired by the skills and craftsmanship of the early printers. However, we’re not looking at a page in a book, not even one limited to 436 copies. This is something far rarer, which was issued separately three years before the publication of the complete work, and which differs from the final version. This is a specimen leaf, one of a handful of copies circulated in 1893 to drum up interest (and subscriptions) for what would prove to be William Morris’ last great project.

The full story appears in the annotated list of all the books published by the Kelmscott Press accompanying a collection of William Morris’ essays, which appeared posthumously (1902) as The Art and Craft of Printing. It seems that “Mr. Morris began designing his first folio border on Feb. 1, 1893, but was dissatisfied with the design and did not finish it. Three days later he began the vine border for the first page, and finished it in about a week, together with the initial word ‘Whan,’ the two lines of heading, and the frame for the first picture, and Mr. Hooper engraved the whole of these on one block. The first picture was engraved at about the same time. A specimen of the first page (differing slightlyfrom the same page as it appears in the book) was shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893, and was issued to a few leading booksellers…”

The main picture was one of eighty-seven designed by Morris’ great friend Sir Edward Burne-Jones; it was Burne-Jones who wrote “If we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral”.

Specimen leaves were produced for other Kelmscott Press books, sometimes in large numbers. 2000 copies of a quarto prospectus for The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (the first appearance of the black letter ‘Troy’ type used in the Chaucer) with specimen pages, were printed at the Kelmscott Press in December 1892. This appears to have been an entirely different proposition, circulated among “a few leading booksellers” and exhibited at the fourth Arts and Crafts Exhibition (Morris had succeeded Walter Crane as President of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society). It may originally have been a bifolium, so the first pair of leaves (ie four pages) of text, but if so an early owner seems to have decided to divide it and frame the first leaf; perhaps the second was framed alongside it, but it is now lost. The only other example which I have seen does not have ‘specimen’ printed in red in the lower margin, but the setting of the text was identical.

The setting of the text allows us a glimpse of Morris’ thought processes at work. He decided that the large initial was too close to the printed border above it, and dropped it down a line to leave white space. In the final printed version there are six, not seven lines of text beneath it, and the setting of the rest of the text reflects the change.

Back to our annotated list: “On May 8 <1896>, a year and nine months after the printing of the first sheet, the book was completed. On June 2 the first two copies were delivered to Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Morris”. Burne-Jones was right to be concerned for his friend’s health (he worked feverishly to complete the illustrations, devoting every Sunday to them). Morris died on October 4, the opening day of the fifth Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

This is one of those artefacts which communicates the thrill of creation, something of the excitement and anticipation which Morris and Burne-Jones must have felt as these first trial sheets were pulled from the press.

The full story appears in the annotated list of all the books published by the Kelmscott Press accompanying a collection of William Morris’ essays, which appeared posthumously (1902) as The Art and Craft of Printing. It seems that “Mr. Morris began designing his first folio border on Feb. 1, 1893, but was dissatisfied with the design and did not finish it. Three days later he began the vine border for the first page, and finished it in about a week, together with the initial word ‘Whan,’ the two lines of heading, and the frame for the first picture, and Mr. Hooper engraved the whole of these on one block. The first picture was engraved at about the same time. A specimen of the first page (differing slightlyfrom the same page as it appears in the book) was shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893, and was issued to a few leading booksellers…”

The main picture was one of eighty-seven designed by Morris’ great friend Sir Edward Burne-Jones; it was Burne-Jones who wrote “If we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral”.

Specimen leaves were produced for other Kelmscott Press books, sometimes in large numbers. 2000 copies of a quarto prospectus for The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (the first appearance of the black letter ‘Troy’ type used in the Chaucer) with specimen pages, were printed at the Kelmscott Press in December 1892. This appears to have been an entirely different proposition, circulated among “a few leading booksellers” and exhibited at the fourth Arts and Crafts Exhibition (Morris had succeeded Walter Crane as President of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society). It may originally have been a bifolium, so the first pair of leaves (ie four pages) of text, but if so an early owner seems to have decided to divide it and frame the first leaf; perhaps the second was framed alongside it, but it is now lost. The only other example which I have seen does not have ‘specimen’ printed in red in the lower margin, but the setting of the text was identical.

The setting of the text allows us a glimpse of Morris’ thought processes at work. He decided that the large initial was too close to the printed border above it, and dropped it down a line to leave white space. In the final printed version there are six, not seven lines of text beneath it, and the setting of the rest of the text reflects the change.

Back to our annotated list: “On May 8 <1896>, a year and nine months after the printing of the first sheet, the book was completed. On June 2 the first two copies were delivered to Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Morris”. Burne-Jones was right to be concerned for his friend’s health (he worked feverishly to complete the illustrations, devoting every Sunday to them). Morris died on October 4, the opening day of the fifth Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

This is one of those artefacts which communicates the thrill of creation, something of the excitement and anticipation which Morris and Burne-Jones must have felt as these first trial sheets were pulled from the press.

The full story appears in the annotated list of all the books published by the Kelmscott Press accompanying a collection of William Morris’ essays, which appeared posthumously (1902) as The Art and Craft of Printing. It seems that “Mr. Morris began designing his first folio border on Feb. 1, 1893, but was dissatisfied with the design and did not finish it. Three days later he began the vine border for the first page, and finished it in about a week, together with the initial word ‘Whan,’ the two lines of heading, and the frame for the first picture, and Mr. Hooper engraved the whole of these on one block. The first picture was engraved at about the same time. A specimen of the first page (differing slightlyfrom the same page as it appears in the book) was shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893, and was issued to a few leading booksellers…”

The main picture was one of eighty-seven designed by Morris’ great friend Sir Edward Burne-Jones; it was Burne-Jones who wrote “If we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral”.

Specimen leaves were produced for other Kelmscott Press books, sometimes in large numbers. 2000 copies of a quarto prospectus for The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (the first appearance of the black letter ‘Troy’ type used in the Chaucer) with specimen pages, were printed at the Kelmscott Press in December 1892. This appears to have been an entirely different proposition, circulated among “a few leading booksellers” and exhibited at the fourth Arts and Crafts Exhibition (Morris had succeeded Walter Crane as President of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society). It may originally have been a bifolium, so the first pair of leaves (ie four pages) of text, but if so an early owner seems to have decided to divide it and frame the first leaf; perhaps the second was framed alongside it, but it is now lost. The only other example which I have seen does not have ‘specimen’ printed in red in the lower margin, but the setting of the text was identical.

The setting of the text allows us a glimpse of Morris’ thought processes at work. He decided that the large initial was too close to the printed border above it, and dropped it down a line to leave white space. In the final printed version there are six, not seven lines of text beneath it, and the setting of the rest of the text reflects the change.

Back to our annotated list: “On May 8 <1896>, a year and nine months after the printing of the first sheet, the book was completed. On June 2 the first two copies were delivered to Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Morris”. Burne-Jones was right to be concerned for his friend’s health (he worked feverishly to complete the illustrations, devoting every Sunday to them). Morris died on October 4, the opening day of the fifth Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

This is one of those artefacts which communicates the thrill of creation, something of the excitement and anticipation which Morris and Burne-Jones must have felt as these first trial sheets were pulled from the press.

The full story appears in the annotated list of all the books published by the Kelmscott Press accompanying a collection of William Morris’ essays, which appeared posthumously (1902) as The Art and Craft of Printing. It seems that “Mr. Morris began designing his first folio border on Feb. 1, 1893, but was dissatisfied with the design and did not finish it. Three days later he began the vine border for the first page, and finished it in about a week, together with the initial word ‘Whan,’ the two lines of heading, and the frame for the first picture, and Mr. Hooper engraved the whole of these on one block. The first picture was engraved at about the same time. A specimen of the first page (differing slightlyfrom the same page as it appears in the book) was shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893, and was issued to a few leading booksellers…”

The main picture was one of eighty-seven designed by Morris’ great friend Sir Edward Burne-Jones; it was Burne-Jones who wrote “If we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral”.

Specimen leaves were produced for other Kelmscott Press books, sometimes in large numbers. 2000 copies of a quarto prospectus for The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (the first appearance of the black letter ‘Troy’ type used in the Chaucer) with specimen pages, were printed at the Kelmscott Press in December 1892. This appears to have been an entirely different proposition, circulated among “a few leading booksellers” and exhibited at the fourth Arts and Crafts Exhibition (Morris had succeeded Walter Crane as President of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society). It may originally have been a bifolium, so the first pair of leaves (ie four pages) of text, but if so an early owner seems to have decided to divide it and frame the first leaf; perhaps the second was framed alongside it, but it is now lost. The only other example which I have seen does not have ‘specimen’ printed in red in the lower margin, but the setting of the text was identical.

The setting of the text allows us a glimpse of Morris’ thought processes at work. He decided that the large initial was too close to the printed border above it, and dropped it down a line to leave white space. In the final printed version there are six, not seven lines of text beneath it, and the setting of the rest of the text reflects the change.

Back to our annotated list: “On May 8 <1896>, a year and nine months after the printing of the first sheet, the book was completed. On June 2 the first two copies were delivered to Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Morris”. Burne-Jones was right to be concerned for his friend’s health (he worked feverishly to complete the illustrations, devoting every Sunday to them). Morris died on October 4, the opening day of the fifth Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

This is one of those artefacts which communicates the thrill of creation, something of the excitement and anticipation which Morris and Burne-Jones must have felt as these first trial sheets were pulled from the press.

Leave a comment