Still Minding The Gap

Our recent posts about the lives of some of the less well known makers of London Underground maps generated a flurry of very pleasant correspondence. Thank you! This piece is all about encouraging even more of it, especially if you have any information about anyone who made maps for London Transport and its predecessors – we'd really like to hear from you.

It’s always been my instinct, when I see a map, to try and discover who made it. Leaving things ‘anon’ goes against the grain, and even when we have a name I’m often surprised to discover how little is known beyond that – sometimes a name and initials and nothing more. I also find contemporary (and later) responses to the published maps of great interest, but for me unearthing the biographical details of the people who made them is more than a question of dotting i’s and crossing t’s. A quick plug here for one of the most useful and insightful reference works of recent years, ‘A Dictionary of British Map Engravers’ (2011) by Laurence Worms and Ashley Baynton-Williams. I read it with great excitement when it first came out and have kept a copy to hand ever since. Yes, there was the general pleasure of ‘meeting’ the people responsible for maps I have handled regularly in my working life, but learning about their circumstances and the circles in which they moved has also given me a greater understanding of their output: why they were commissioned, risked their own capital in uncharted waters or, indeed, sometimes disappeared abruptly from the cartographic record. One of the most original features of the book, enabled by extensive biographical research, was a series of ‘family trees’ revealing how leading engravers in every generation were linked to their predecessors through apprenticeships. Suddenly, through elaborate chains of ‘who taught whom’, the whole world of British map engraving made a great deal more sense.

Can we achieve something similar here? It’s early days, but I think that patterns are already forming. In particular, there seem to have been two clear strands to map commissioning policy: enthusiastic members of staff, who were officially employed in other capacities, or professional artists and graphic designers, some of whom were more established than others. That last point reflects the Underground’s general policy towards poster design: under the aegis of Frank Pick the Underground developed a tradition of encouraging young artists on the way up, as well commissioning the big guns. But this amateur/professional split also suggests that maps have always occupied an ambivalent space in official thinking, even within an organisation which prided itself on considering the design of every last detail, from the tiling to patterned seat covers.

Maps are the most obvious physical expression of the extent of the network (often including any proposed expansion), they are an essential component of journey planning for almost all passengers, and throughout the 20th century they were issued free in a convenient format for passengers to use and take home. They are integral to public perceptions of the Underground. Ask people how they navigate around London, and many will refer to the Tube map. This isn’t a new (or even post Beck) phenomenon. In June 1929 the Derby Telegraph suggested that visitors to the capital

"...may welcome one tip. The most swift and satisfactory method of acquiring a working knowledge of the Metropolis is to get a free Underground Railways map at one of the stations and memorise the great underground traffic arteries by their appearance on the map."

London Whispers

In this pre diagram era, the author was praising the (now) much disparaged ‘vermicelli’ of the geographical designs. And yet, throughout this entire period, maps often seem to have been approached by officialdom as a bit of an afterthought. Given the amount of helpful advice Beck received over the years, there may also have been a general underlying feeling that anyone could ‘do’ maps really. I think that knowing more about the map-makers themselves will help us understand this process better.

So, this project is definitely ongoing. Here are a few more snippets of information for everyone who enjoyed the earlier blog posts. I’ve been investigating William Edward Soar’s numerous family (7 children; thank goodness he was comfortably off when he died: the £2683 he left in 1912 is the equivalent of a chunky six figure sum today – perhaps touching seven figures if we look at it in terms of spending power). And here is an image of the presentation inscription I mentioned, the only one I’ve seen on an Underground map to date.

from William Edward Soar (‘the author’) to A. Pickard Esq, dated 1890.

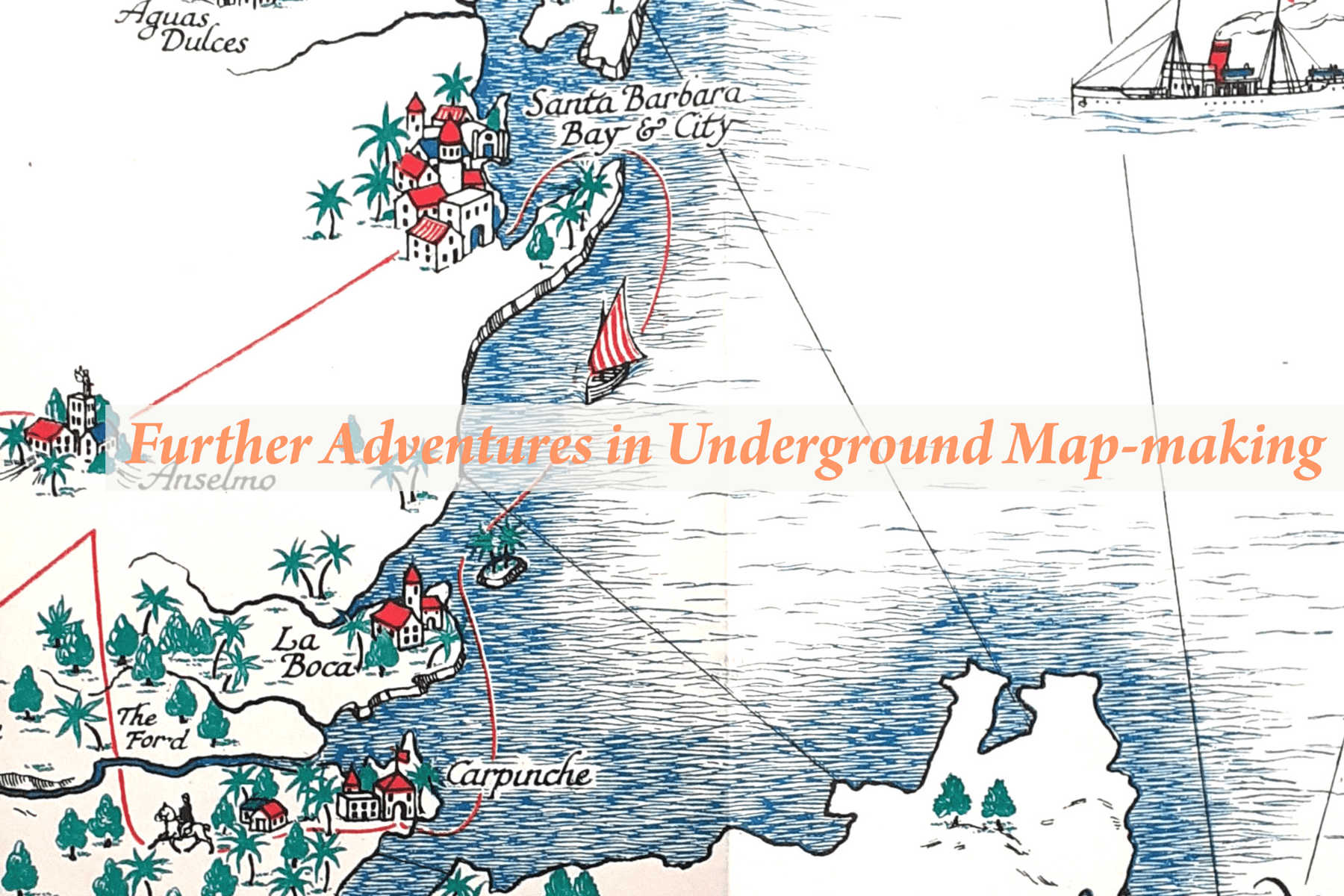

I’ve tracked down more of Edgar George Perman’s 1920s commissions, all cartographic so far, including the elusive Shell advertisements and a dustwrapper he designed for John Masefield’s 1926 adventure novel ODTAA ('one damn thing after another'), which is set in Central America. We only know about it because a signed limited edition of 275 copies was issued simultaneously; a copy of the map was printed on japanese vellum and loosely inserted, which was signed by Perman. He may have designed other dustwrappers anonymously, or initialled (‘EGP’). Please say if you spot one! He also did some work for the Sun Engraving Co, Ltd and designed a rather fine quad royal sized poster for the GWR in 1929, ‘The Gateway to the Continent’ printed by McCorquodale. There doesn’t appear to be an example in the National Railway Museum, but Onslow’s auctioneers sold one back in 2010. It is markedly different from the 1928 poster by T.D. Kerr with the same slogan.

Here are details of some press advertisements designed by Perman for Shell, circa 1924, followed by a detail of the dustwrapper for Masefield’s ODTAA, which includes Perman’s signature. He does seem to have been known for maps.

Perman is coming along nicely, but the 1930s are still a blank, other than his rather amateurish involvement with the ‘Flying Flea’ craze, which was vividly described (as I’d hoped) in the autobiography of test pilot A.E. Clouston. Perman isn’t named, but Frank Broughton is. Broughton was a printing works foreman who collaborated with Perman on the development of the ‘Perman Parasol’ otherwise known (in various iterations of its evolution) as the Perman Grasshopper, Clouston Midget and Broughton-Blayney Brawny. In spite of improvements and changes in nomenclature, the common trait shared by these light aircraft was that they were potentially lethal. Perman’s father Arthur had managed successful engineering projects while Traffic Superintendent of Government Railways in Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and his younger brother Archibald established the engineering firm 'Perman and Co, Ltd'; one wonders if they offered assistance or advised him to stick to art…

Benjamin Getzel Lewis promises to be extremely interesting. He was the closest the mid century Underground had to an ‘in house’ cartographer. ‘Ben Lewis still does the cartography’ wrote Bryce Beaumont from the London Transport Publicity Office to artist John Fleming on 16 October 1956. Beaumont was giving him news of old friends – which included news of Harry Beck. No mention of Beck’s freelance work on the diagram though, or any association with London Transport: ‘Harry Beck still teaches at the London School of Printing’. It was a casual remark, but rather telling: for Beaumont, Hutchison’s deputy in the Publicity Office, Lewis was the man who made the maps. This poster was designed by Benjamin Geztel Lewis to advertise the opening of the Piccadilly Line extension to Cockfosters in July 1933. He seems to have begun working for the Underground c.1931.

Lewis’ parents and older siblings were born in Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire, and they arrived in the East End of London sometime between the births of Ashley (1888/1889) and Isaac (1890); the family was part of a wave of emigration from Russian Poland which took place in the aftermath of the anti-Jewish pogroms of 1881-84. The name Lewis was almost certainly chosen on arrival to sound more English. I’ve heard that names were sometimes chosen at random, but it might possibly be an Anglicisation of a Jewish name such as Levi. The 1911 census shows Lewis’ widowed mother Sarah living at 91 Old Montague Street with ‘Benny’ (his father Jacob died in 1903); two older brothers were working as tailors, and one as a printer. Old Montague Street was coloured very dark blue on ‘Jewish East London’, a folding statistical map which was tipped in at the beginning of ‘The Jew in London’, a book produced under the auspices of the pioneering social reformers at Toynbee Hall.

By the standards of its day the book attempts to present a measured discussion of the impact of the wave of migration which included the Lewises: the emphasis was on addressing social issues such as reducing overcrowding and improving insanitary living conditions rather than on restricting immigration. One of the two authors was a Lewis himself, though I have no reason for thinking him a relation of our Lewises: Harry Samuel Lewis was a Cambridge-educated Jewish social reformer working from Toynbee Hall among the Jews of the East End. The book, with its vivid descriptions of the streets where the Lewises had made their home, happens to have been published in 1901, the year that Benjamin Lewis was born. And the blue on the map? Though relying heavily on the methodology devised by Charles Booth (and executed by some of the same people) it is a deeply flawed map which Tom Harper and I wrote about more fully in ‘A History of the 20th Century in 100 Maps’ (British Library, 2014). Very dark blue denoted streets with 95%-100% Jewish population, and for anyone familiar with Booth’s maps that shade of blue was associated with the category ‘vicious, semi-criminal’ (although as Tom and I noted, on Booth’s actual ‘poverty maps’ the streets with the greatest density of Jewish inhabitants were far from the poorest; they were mostly coloured to indicate ‘wealth and poverty (mixed)’, and Old Montague Street was no exception). The survey on which the map was based was made in 1899, and one can readily picture Lewis’ family living ‘on the map’.

I haven’t been neglecting Harold Hutchison either. I’ve been reading back issues of his school magazine, which he edited in 1918. Like his brothers before him, he became the senior boy in his school’s Officer Training Corps, and there were more tales of his sporting prowess: he gained his football and cricket colours when he went up to Oxford. It all sounds a bit ‘Stalky & Co’ to me, but I can’t help casting covetous eyes at some of the places he lived. He was a life member of his old boys’ association, and in 1935 the school magazine gives his address as 6 Cholmely Lodge, Highgate. According to the electoral register he was still there with his wife Nellie in 1938, although in 1939 they decamped to Amersham (Metro-Land for the duration, I wonder?) These glorious Art Deco flats were built in 1934, so Hutchison moved in when they were brand new. If the style looks familiar it may be because the architect, Guy Morgan, also designed Florin Court – the setting for Poirot’s flat in the television series starring David Suchet.

As the maps we’re looking at were all made within the last 150 years there’s a very real possibility of hearing from family members of the people who made them. That was certainly (and wonderfully) the case when I started working on Kerry Lee, a maker of pictorial maps previously referred to in online institutional catalogues as ‘poster artist, active 1950s'. All of a sudden we had photographs, reminiscences and original artwork, transforming our understanding of the man and his work. If anyone can help with information about any maker of London Underground maps, however slight it might seem, please get in touch.

Leave a comment