4-line Whip: A UERL Mapping Mystery

We’ve written before about how the first colour coded, passenger-friendly maps of the London Underground system were issued by the Evening News, a London newspaper, rather than officially by the Underground Group. London’s underground railways were built by competing private companies, which were more interested in encouraging passengers to use their lines than to change trains and use the Underground as a comprehensive network. Their maps emphasised their own lines over their rivals’, at the expense of clarity and ease of use.

Even the UERL, with four lines under the same umbrella organisation, fell into the same trap. Their early maps show UERL lines coloured red, or in bold on monochrome maps, to set them apart. After the Evening News map was issued in April 1907 the UERL swiftly commissioned their own colour coded map of the system, and circa 1912 even hired the same cartographer, George Philip and Son, Ltd, to produce a version in the UERL house style with a green border.

The Evening News was not the only company making unofficial Underground maps in Edwardian London. In the 1920s and 1930s it would have been more common for businesses to have their location and other details overprinted on the official passenger maps – seemingly encouraged by the Underground group for firms of all types and sizes as useful promotion. That lay in the future, and without a standard passenger map some firms commissioned their own. However, what has surprised me so far is that other non-UERL maps seem to stick exclusively to UERL lines.

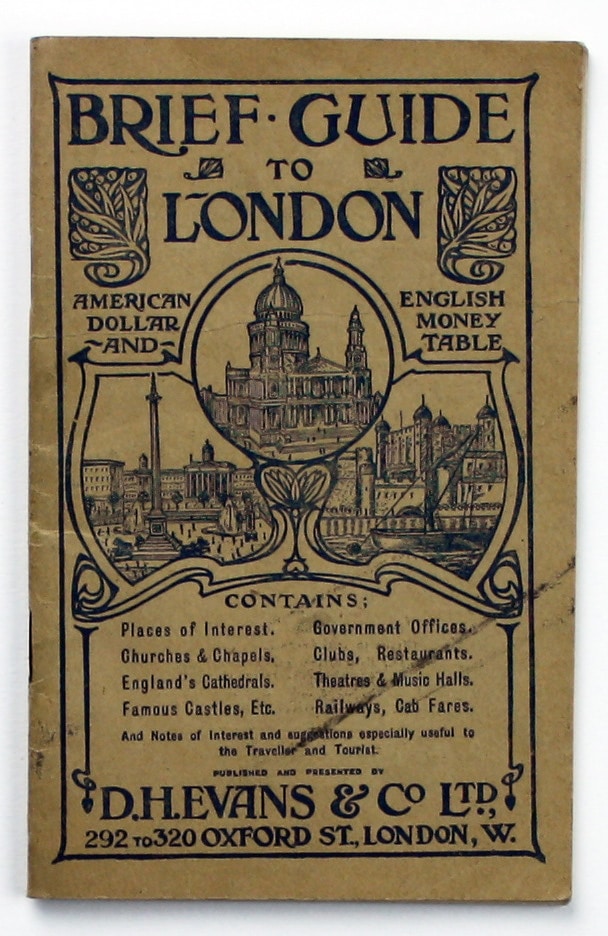

I have two examples of a Brief Guide to London issued by the Oxford Street department store D.H. Evans, in 1908 and 1911. Both have a specially commissioned folding map pasted to the inside lower cover, designed by the Dewynters Press and printed by Bonnett and Shum. They are printed in three colours with some landmarks depicted pictorially, including the D.H. Evans department store – which is highlighted in red, more or less at the centre of the map.

The differences between the maps are minor. The Anglo-French Exhibition (swiftly renamed and more generally known, even in the text of the accompanying guide, as the Franco-British Exhibition) is shown at White City, with a French tricolour fluttering above. The words ‘Anglo-French’ and all save one line of the tricolour have been erased from the later example. The Bakerloo Line extension to Paddington opened in December 1913, and it is shown on both maps as under construction. Oxford Circus, which had separate ticket halls for the Bakerloo Line and the Central London Railway until 1923, is shown as two separate stations.

There is no key, but efforts have been made to differentiate between the different types of line. The three deep level ‘tubes’ under the UERL aegis, precursors to the modern Bakerloo, Northern and Piccadilly Lines, have stations marked with a circle. The UERL was also the parent company of the cut-and-cover District Line, whose stations are marked with squares. It isn’t immediately clear if the map-maker wanted to differentiate between the UERL’s administrative arrangements or the construction methods, but perhaps the new deep level tube lines were still enough of a novelty to make the latter more likely.

The mystery remains of why D.H. Evans commissioned a map which only showed the UERL lines. As the District Line is shown, it clearly isn’t enough to say that the others, such as the Metropolitan Line, couldn’t be considered ‘tubes’, and the Evening News had happily included them all on its London “tube map”. Answers on a postcard, please!

I haven’t found any clues in the guides as yet, although they were useful for dating purposes. The 1908 example refers to the Franco-British exhibition and the Olympic Games; the 1911 edition advertises the Coronation Exhibition and Empire Display at White City, and the Festival of Empire at Crystal Place (‘probably’ to run May to October, so the guide may have been printed in late 1910 before dates were fixed). For the rest, the guides contain useful information for travellers and tourists which is more or less identical, such as plans of London theatres. Both have several pages devoted to touring British cathedrals, which is curious in a London guide, but whether that was a particular obsession of one of the directors of D.H. Evans or was thought to appeal to the target audience it’s now impossible to say. As for the target audience, several pages are also devoted to converting prices in pounds, shillings and pence into dollars, and the advertisement for D.H. Evans on the back cover explains ‘why American ladies should shop in London and free-trade England… rather than high-protection France’.

Regent Street department store Dickins and Jones also produced promotional tube maps for its customers on a very similar model.

Thanks to Jim Whiting, who has been kind enough to share an image of this example from his collection, dated to circa 1907.

Leave a comment