A Small Specimen of the Biggest Map: Fundraising for Horwood's Monumental Plan of London

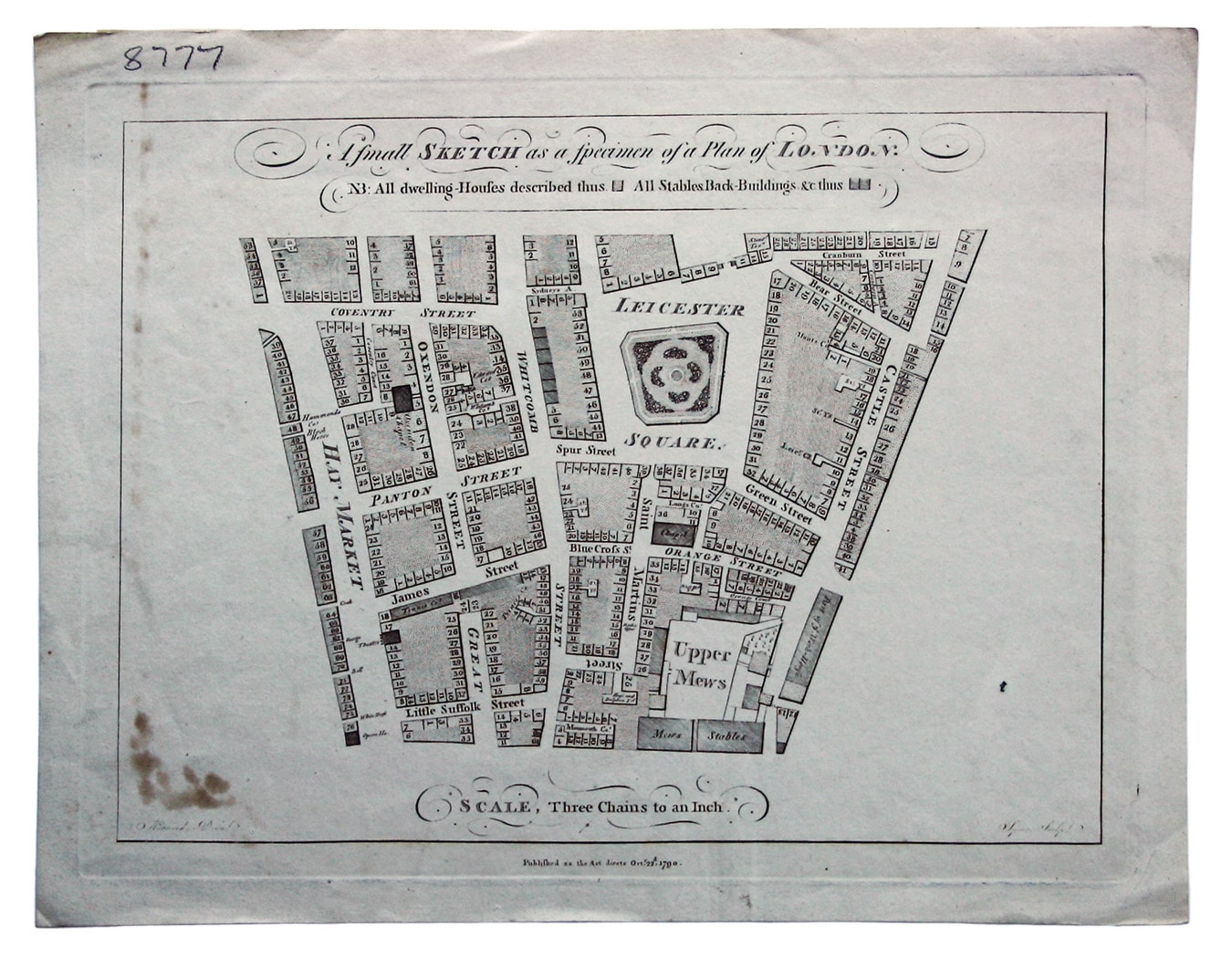

We have just purchased an extremely scarce little map of Leicester Square and the surrounding streets. It’s of local interest to us here in Cecil Court, but it is also tied to one of the great Georgian mapping projects, Richard Horwood’s monumental plan of London, published 1792-1799.

Making money from maps has never been easy, and creating new maps (rather than copying other people’s) has all too often been a milestone on the road to bankruptcy. The Bowens (father and son), Thomas Jefferys, the Greenwood brothers, and even John Tallis, creator of the hugely popular Illustrated Atlas, all followed the same path.

Unfortunately Richard Horwood was no exception; a brilliant original map-maker, he died in penury. Around 1790 he conceived the idea of the biggest map made in Britain to that time, 32 individual map-sheets measuring over 4 metres wide by 2 metres tall when joined. It was to be a survey of London on the same scale as John Rocque’s map of half a century before, but the population had grown from approximately three quarters of a million to a million (London was well on the way to overtaking Beijing as the largest city in the world), and this was accompanied by a good deal of urban sprawl.

The project took almost ten years, rather than the estimated two, and Horwood was desperately trying to raise funds throughout. This rare little map, A small sketch as a specimen of a plan of London, was part of the process.

It measures just 18.5 x 24 cm, but it conveys the level of detail to be expected from the full-size map. Horwood was the first to show individual house numbers. Numbering began in London in the 1760s, if not before (although house numbers were not used in official records until much later – the 19th century in some cases) but Horwood was the first to mark them on the map. Horwood claimed that he ‘took every angle, measured almost every line and after that plotted and compared the whole work’ in person.

It was engraved for Horwood by Richard Spear. Spear also engraved four of the map-sheets of the main map, but he is not known to have engraved any other maps. Other sheets were engraved by ‘J.T.’ tentatively identified by Worms and Baynton-Williams in their indispensable British Map Engravers (2011) as John Thompson of Gutter Lane, who again was not widely known as a map engraver. It would be interesting to know more of Horwood’s relationship with the map trade of the time.

The maps, large and small, reveal the changing face of patronage. Earlier map-makers such as William Morgan looked to royal or aristocratic patrons to shoulder the costs of their original, large-scale surveys, and in the mid 18th century John Rocque was sponsored by the Aldermen of the City of London, but Richard Horwood's principal backer was the Phoenix Fire Company, an insurance firm. He also relied on private subscriptions.

To that end, our little map was issued with a single sheet prospectus in 1790: ‘Richard Horwood, land-surveyor, respectfully informs the gentlemen of the vestry of the parish of

That appears to be the sum total of institutional holdings, although there may be other examples which have fallen through the cataloguer’s net. It was clearly an ephemeral, disposable item and very few seem to have survived.

I began by mentioning that Leicester Square is local for us (the entrance to Cecil Court can be seen in the upper right hand corner of the map) and of course I’m curious as to why Horwood chose this part of London to advertise his full-size map. Horwood lived in Mare Street, Hackney, and his backers at the Phoenix Fire Company had offices nearby at Charing Cross, but they’re not on the map either. Leicester Square was no longer home to royalty in 1790, and although it retained vestiges of its former fashionable self, it was becoming known as a venue for entertainment. At the time Horwood prepared his specimen map it was the proposed site of a new Royal Opera House (never built), backed by the Prince of Wales, and perhaps that is what put it in Horwood’s mind.

Updated 23/10/2017:First of all, I’ve been comparing the specimen with the finished, full-size map. Leicester square may have been chosen for the specimen, but it was on one of the last map sheets to appear in finished form, dated May 24 1799. Most of the changes may have been due to redevelopment over a ten year period (for example, the appearance of Leicester Place in the northeast corner of Leicester Square, and perhaps the slightly more angular layout of the gardens in the square). There are stylistic differences too, to the lettering of the ‘Upper Mews’, for example.

Anne Taylor of Cambridge University Library has identified a second specimen map in the collection there, featuring the Cavendish Square area. Any potential imprint has been trimmed away and the main body of the map is unsigned and undated so it has not been possible to establish priority, but Horwood evidently felt it worthwhile to have two specimens in circulation.

And finally, my friend Laurence Worms found Richard Spear’s trade-card; he was located over in the City.

Leave a comment