Pictorial Plans of London: MacDonald Gill & beyond

This post is something of a work in progress, so please check back now and again to see if I’ve been able to expand it. So far I’ve tried to avoid some of the most well-known maps, but in this instance there’s no excuse for not beginning with MacDonald Gill’s playful and eccentric Wonderground map of London. Apologies if you know it already, but it always repays another look:

Gill’s map was commissioned by London Transport in 1913, and was so successful that it was offered for sale to the general public the following year. The map I have here is an example of that issue: The heart of Britain’s Empire here is spread out for your view … You have not time to admire it all? Why not take a map home to pin on your wall! And of course, most purchasers took Gill’s advice and did just that, which is why it has become scarce today … With this map Gill inspired a whole genre of comic map-making, filling his map with poems, puns and in-jokes (some bad, a few inexplicable). One needs hours to ‘admire it all’ (unscramble might be a better word). Here’s how Gill treated one of my favourite places in London, the zoo:

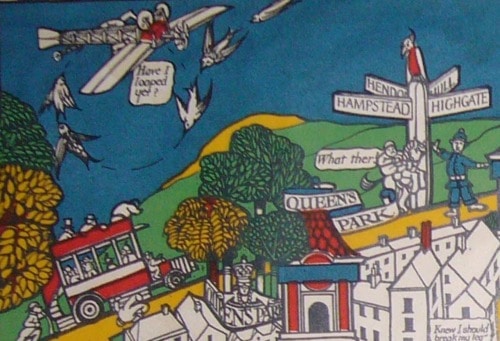

It’s a much more entertaining way of showing how the Underground Stations relate to surface topography than anything dreamt up previously, but the style is better suited to pleasure than business and I note that most maps of this genre focus on West London rather than the City or the East End. The blend of old and new seems typically Edwardian, summed up in this detail from the upper left corner:

The curvature of the horizon is decidedly medieval (Arts and Crafts, anyway), while the aeroplane and motorized omnibus bring us firmly into the Twentieth Century. The speech bubbles are Gill’s own. Gill went on to create further maps for London Transport, including a series of ‘straight’ pocket Underground maps in the 1920s; he also designed the font used on headstones by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and numerous posters for bodies such as the Empire Marketing Board. I suspect that he was more commercially successful than his brother, Eric. A new carto-bibliography of his work is expected soon (following last year’s MacDonald Gill exhibition in Brighton), and in the meantime I refer you to Elisabeth Burdon’s excellent article.

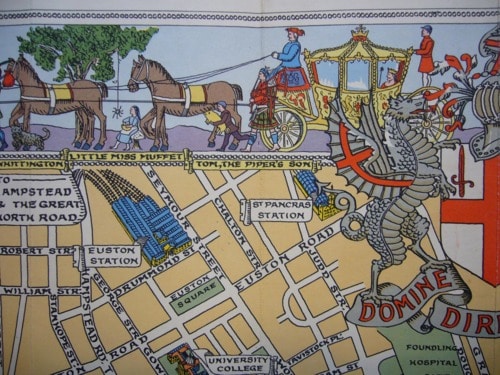

Update: in early 2014 Winfrid de Munck and I wrote more about the different states of Gill’s map. I’d like to devote the rest of this post to other maps which were show clear signs of being influenced by Gill’s work. This map is more blatant than most:

Published by Alexander Gross’s firm, Geographia Ltd in the 1930s, it’s unsigned.

The visual and verbal puns (the long arm of the law reaching out from Scotland Yard, the ink spilled on Fleet Street …) and historical and topographical notes are typical of Gill’s work. But Gill it most certainly isn’t. Mind you, it was popular enough for Geographia to issue it in jigsaw form:

My friend Winfrid de Munck has an example with a different border and initials in the lower right hand-corner; an ownership inscription is dated July 1934:

I read that as W.J.H. - hopefully it will be possible to identify the artist in due course. Below is the standard Geographia London Pictorial Map, published in numerous editions between the 1920s and 1950s

Not terribly inventive, perhaps, but worth including as the early post-war editions are among the only maps to show the blitzed area in the City of London:

The area left blank on the map had almost reverted to the heathland it had been centuries before, carpeted with rosebay willowherb and ragwort. Some streets could only be identified from temporary wooden signboards. Leaving the map blank seems entirely logical - it’s surprising how few cartographers followed suit. It may simply have been a desire to maintain a sense of normality. It isn’t easy to find signs of bomb damage on the Bond Panorama either, published by the Baynard Press in 1944.

Bank of England employee and artist Arthur Bond was an ARP observer on the roof of the Bank during the second Blitz; V-weapons were unleashed against the capital for the first time in June 1944. According to the Bank of England’s own website, the Bond Panorama was printed in 200 copies which were given to members of staff who had also served as firewatchers. Bond’s 360 degree panorama of the London skyline, as seen from his observation post, borders a reworking of the Ordnance Survey map, with a one mile radius around the Bank. Significant buildings can be located from the key using degrees. The Baynard Press was a commercial printer noted for the quality of its colour lithography, with clients including London Transport. Here’s Leslie Bullock’s Children’s Map of London, c. 1938:

Bullock worked closely with Edinburgh publisher John Bartholomew and Son over a long period. All royalties for this map were donated to Great Ormond Street Hospital. In the margins are nursery rhyme scenes and the map is flanked by the Biblical giants Gog and Magog, long associated with London.

There are scattered quotations, but the map is not as crowded as Gill’s (I suspect Bullock lacked Gill’s talent for whimsical quippery). However, there are echoes of Gill’s work here - I doubt Bullock’s map would have existed without it. Update: In 2014 I wrote more about Bullock’s work. I’m also going to include Kennedy North’s 1923 British Empire Exhibition map:

North’s debt is principally calligraphic - the lettering is clearly inspired by Gill’s 1920s Underground maps - although one might also look at the bold use of colour and details such as the buses, cars and trams. Note North’s impressive attempt to reduce the Underground system to diagrammatic form almost a decade before Harry Beck.

I’ve been assuming that Kennedy North is Stanley Kennedy North: artist, illustrator, picture restorer, socialist, folk dancer and general bohemian. Commercial work (e.g. for Shell Oil) seems to be signed simply ‘Kennedy North’, but it seems unlikely that there would be two similarly named artists working at the same time. If I spot a definite link I’ll update this entry.

Leave a comment