Provenance-On-Sea: A Coastal Pilot's Tale

The atlas in front of me has quite a story. Published at the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars, this is a British-produced pilot book. It's a marine atlas with charts, coastal profiles and descriptive text, which in this case covers the French and Italian coastlines as far south as Naples. It belonged to the sculptor Anne Damer and it seems highly likely that she took it with her to Naples in 1798, when she visited her friends Sir William Hamilton and his wife Emma, and met Nelson. We can trace the book’s later ownership over the next half century: well within Damer's lifetime the atlas had passed into the hands of a family of silk dyers in Coventry, with no obvious connection with her, but with strong connections to trade with France. The chain of provenance raises intriguing questions about how the atlas passed from a wealthy, aristocratic traveller into the hands of a modest Coventry merchant with French connections, but we can only speculate.

No two copies of an old book or map are exactly the same. Working archaeologically through the layers which make up the history of a physical book, such as its binding and marks of ownership, and piecing them together, can be enormously revealing about the readership, real and intended, and how it was actually used. It isn’t always what we expect.

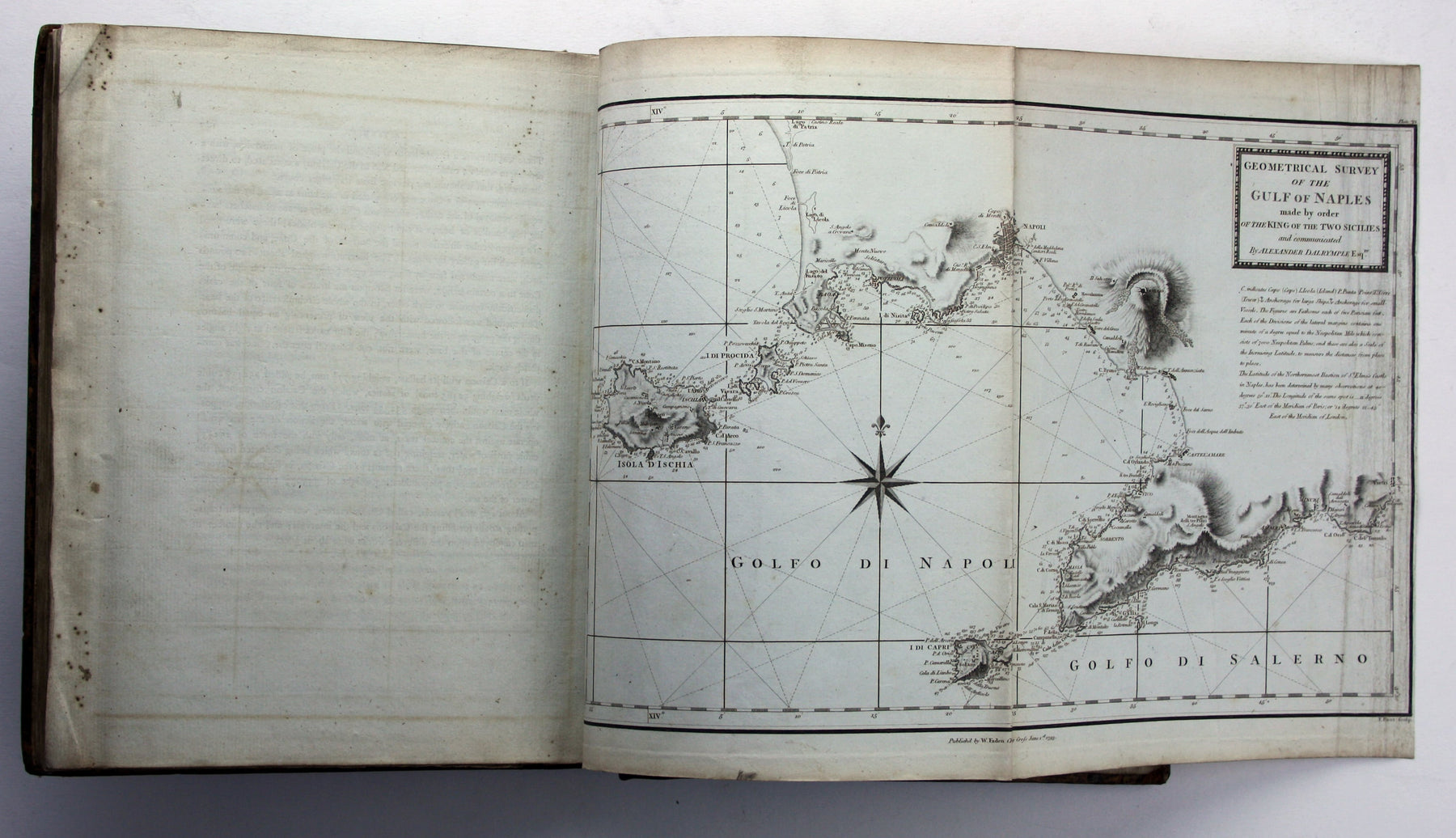

Let’s start with what the book is, Published in London by William Faden in 1793 it is a sturdy quarto: “Le Petit Neptune Français; or, French Coasting Pilot, for the Coast of Flanders, Channel, Bay of Biscay, and Mediterranean. To which is added, the Coast of Italy from the River Var to Orbitello; with the Gulf of Naples, and the Island of Corsica; illustrated with charts, plans, &c.”

It opens with an engraved frontispiece view of the Tower of Cordouan (the oldest lighthouse in France, near the mouth of the Gironde estuary) and contains 46 black and white engraved charts on 39 sheets, mostly folding, with three further sheets of coastal profiles. It is bound in a contemporary binding, tree calf with classical key pattern border, now rebacked but preserving the original spine. There’s our first clue: this would not have been a cheap book, given its numerous illustrations, but it is a practical one for use in navigation, not a specimen of fine typography. One might therefore have expected a cheaper ‘working’ binding. Covered in plain calf perhaps, or made with an even cheaper leather such as sheep. Some marine atlases were bound in limp leather, with no pasteboard to retain moisture. Here the leather has been chemically (and artfully) treated to create the ‘tree’ pattern, and the classical motif picked out in gilt is in the best possible taste for the 1790s. It is all fancier than strictly necessary, but not ostentatiously so. Did it live in a library, or go to sea?

On the front pastedown is the pictorial bookplate of Anne Seymour Damer, an acclaimed sculptor (1748-1828). Dated 1793, it too is contemporary with the atlas. A young woman kneels before a memorial, seemingly to Damer herself, who is named on the plinth, beneath which a laurel wreath encircles a sculptor’s tools. Set above the plinth and flanked by dogs is a shield, featuring a set of wings, fleur-de-lis, annulets and passant lions. Damer would choose to be buried with her sculptor's tools and the ashes of her favourite dog. The bookplate was engraved by Francis Legat (1755-1809) and designed by the painter Agnes Berry, whose sister Mary was one of Damer's closest friends and also almost certainly her lover.

Above the bookplate is an early inscription: ‘Saint Servan près de St Malo, le Bretagne, JWC’; Saint Servan is two miles from St Malo in Brittany, effectively the affluent residential suburb of a busy port with strong trade links to India. JWC was the John Waters Coldicott of Coventry who wrote his name on the rear endpaper. John Waters Coldicott also appears to be responsible for adding co-ordinates of the Saint Malo light by hand on page xv. Here we have to speculate, but he seems likely to have been engaged in an Anglo-French business venture in which an atlas was useful. Beneath Anne Damer’s bookplate on the front pastedown is an 1824 inscription by Coldicott presenting the book to his son, also JW Coldicott, whose printed book label partially obscures it. By this time he was back in Coventry, the book had become a keepsake. A final inscription of the front endpaper records Coldicott junior’s gift of the book to one John Peake in 1854. It evidently remained a cherished possession sixty years after it was printed, by which time some of its maps would have been dangerously obsolete. Most old maps are safe enough, but out-of-date sea charts can be fatally misleading.

The atlas is an adaptation of 'Le petit flambeau de la mer' by the 17th century French map-maker Georges Boissaye du Bocage. Thomas Jefferys published an English version of the atlas with 'large improvements' in 1761, which was a step towards improving the reliability of charts of the French coast available to the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War. A second edition appeared in 1774 under the joint imprint of Jefferys and William Faden; the elder Jefferys died in 1771, deeply in debt, and his son, the younger Thomas Jefferys, went into partnership with William Faden, then a young man himself. By the 1790s Faden was firmly established in his own right, and the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France provided the impetus for a new edition. According to the map historian and bibliographer Rodney Shirley, ‘many of the charts in Faden's Le Petit Neptune follow those in Thomas Jeffery's atlas of the same name of thirty years' earlier. They are however newly engraved with Faden's imprint... and a plate number in the upper right corner’.

So back in the 1790s when the maps were newly revised the book’s earliest recorded owner, Anne Damer, would have found it a useful travelling companion. Damer enjoyed the wealth and social status to travel with relative freedom, even in wartime. She moved in aristocratic Whig circles - she was a close friend and supporter of Charles James Fox - and her art reflected her political beliefs as well as her fascination with classical antiquity. Admired and encouraged by David Hume and Horace Walpole, she became Britain’s first famous woman sculptor, the object of satirical attacks as well as critical recognition. Walpole introduced her to the Berry sisters, and bequeathed her Strawberry Hill (where she was living for at least some of the time that this atlas was in her possession). She travelled to Paris with Mary Berry during the peace of Amiens in 1802, where she met Napoleon and presented him with her busts of Fox and Nelson, but our atlas would have been of limited use for a short hop across the Channel. However, it covers the Italian coastline as far south as Naples, which Anne had first visited in 1780. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography suggests she travelled there again in 1798, where she met Nelson through her old friend Sir William Hamilton and his wife Emma. A recent biographer (Jonathan David Gross, ‘The Life of Anne Damer’ 2013, p. 286) questions whether she returned to Naples in 1798 or met Nelson in London sometime after his arrival there in November 1800. However, Damer’s ownership of this 1790s atlas supports the idea of extended continental travel in this period. It’s just the sort of evidence I’d be looking for, in fact. Nelson certainly sat for her (she complained that he kept moving his head and claimed that hers was the only bust of Nelson sculpted from life) and he gave her the coat which he had worn at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798. As an aside, that also strikes me as a spontaneous gesture, made close to the event.

It is tempting to think that Damer abandoned her atlas on the continent, or gave it away. There is no obvious connection with its next recorded owner, John Waters Coldicott. A John Waters Coldicott is listed as a bankrupt leather seller in Lewis Goldsmith’s fiercely anti-Napoleonic newspaper, the Anti-Gallican Monitor for Sunday 29 June 1811, but he seems to have become a solid enough member of Coventry’s mercantile community. Assuming we are following the same Coldicott and not a close relative, by 1825 he had become a silk dyer: notices in the London Gazette announced the dissolution of partnerships with Joseph Russell in February and Jean Baptiste Vuldy in June. By which time, of course, he had no further need of his atlas and had given it as a memento to his son. France was a centre of the European silk trade, and all we can really say is that Saint Malo is a perfectly logical port for an Anglo-French business to work from. Most of the silk came from inland, from Lyon and the south, but Coldicott may have had his fingers in other pies too and perhaps he used the atlas to check distances and to see if sailing times and costs incurred for his cargoes were reasonable. Coldicott junior also bobs in and out of the newspapers: he seems to have worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company, been thrown into debtors’ prison on the Isle of Man (originally accused of assault by his wife but not tried or convicted, the circumstances surrounding his continued imprisonment for debt were sufficiently murky to be raised in the House of Commons in June 1845) and emigrated to Maine. One would need to take proper time to get one’s Coldicotts in order to be sure, but it is all a far cry from the fashionable, cultivated world inhabited by Anne Damer. It is also a world away for the kind of existence one might have imagined for this atlas, and the one which was probably uppermost in Faden’s mind when he chose to publish it, which was to spend its working life in a officer’s cabin on a British warship, perhaps engaged on the often tedious duty of blockading French ports during the Napoleonic Wars. Provenance is a wonderful thing, especially when it adds to our understanding of how maps were read, used and prized long after their practical value had gone.

Leave a comment